Starters

We’ve all probably heard of Newton’s Laws as children and studied them in school. However, many of us would have either misunderstood them or visualised it wrongly. Most of us even forget it after college, except maybe those that take mechanical engineering. While I was not a student of mechanical engineering, I had visualised it wrongly and it took me a while to understand it intuitively. I also realised how we take physics for granted without really understanding the nuances of nature. Only when I understood it clearly, did I really appreciate it. I’ve been meaning to write about it for quite a while, but never made up time to address it.

This is Part 1 of a series that I’ve decided to write. This part is basically going to tell us why “F = ma”. The next parts will talk about how particles move in specific systems and why the systems on a whole behave they way they do.

Newton’s Laws are the foundations of Classical mechanics. They tell us how particles behave in a system and how they move, given some clues. So, without further ado, let us jump right in!

Let’s try to remember the laws, now shall we?

Newton’s 1st Law: Newton’s Law of Inertia

A particle stays in the same state of motion unless and until it is acted upon by an external unbalanced force. This is the reason things are as they are unless pushed. This applies not just to particles but can be extended to living beings as well. That feeling when you’ve got to get up from your comfy sofa to get that remote, amirite?

While I just breezed through the concept, I will be explaining in more detail in subsequent posts.

Newton’s 2nd Law: Force Law

The response of a particle to a force acting on it, is the time derivative of its momentum. Ah, this law. This is the arguably the most important one, and it’s also the most confusing one. It took me personally a long time to intuitively understand this one.

Momentum is a big word, but trust me it’s got something with the word “moment” as in time. I’ll explain that later, but as of now, let’s picture a ball moving on a table. If you draw its velocity vectors at every point and scale it with a constant called “mass”, you get the momentum vectors at every point.

Momentum is represented by P, and it is mathematically written as: P= mv, where m is mass and v is velocity.

Now hold on! I see I’ve just brushed this off with some science-y words like velocity, vectors and derivative and even if you guys knew what they are I’m pretty sure you guys are probably thinking “Why do we have to the take the velocity and mass and multiply them?”. Well, that I shall cover later as I build your intuition towards it.

- Vectors are quantities which have magnitudes and directions.

- Velocity is basically a quantity that tells one how fast something is moving, and at what direction it’s moving, and by definition it’s a vector.

- Derivative is a fancy word for a measure of change. It tells you how fast something changes.

- Mass represents the object’s inertia, as we saw above, its tendency to be stuck as a lazy bum. Mass doesn’t have a direction so it’s not a vector.

In Part 1, we’re only going to talk about this law considering mass as constant. So, we can consider the output reaction to the input force as F=ma, where a is the time derivative of v, called acceleration. Instead of thinking deeply about momentum, for now let’s just consider the reaction force as this product and ponder over why it is that product.

Newton’s 3rd Law: Law of action and reaction

All forces come in pairs. When two separate bodies interact, force pairs come into play. Since at least two bodies are required for an interaction to have an effect, forces come in pairs.

We could also think of it this way. Force pairs are nothing but an interaction between two things. Thus in order to talk about a force, we need to talk about the two things the interaction is acting between.

It does not seem intuitive that forces must come in pairs. But the fact is, without a minimum of two objects “interacting” with each other, the concept of force doesn’t make sense. It’s often misunderstood that if one exerts force, that one is a ‘source’ of the force and therefore, force requires only one object. But in this case, one is confusing between the concept of ‘force’ and a ‘field’. A field can have one source, whereas a force can not.

I will be highlighting this more in subsequent posts.

Main Course

Alright now bear with me, things are going to sound a lot more maths-y and science-y, but trust me you will have a better idea about this and learn something.

For clarity in discussion, distinctions must be drawn on what is the “input force” and “output force”. The input force applied is a push or a pull applied by a hypothetical contraption; it is mathematically a function of a continuous variable that could be time, position, velocity, acceleration, or some other quantity. Function here implies dependency; the input force being dependent on any of the above mentioned variables. Continuous here implies that there are no breaks in the dependency. The function if continuous, has a value for all values of its parent variables.

The quantity force is a vector quantity; it has both magnitude and direction.

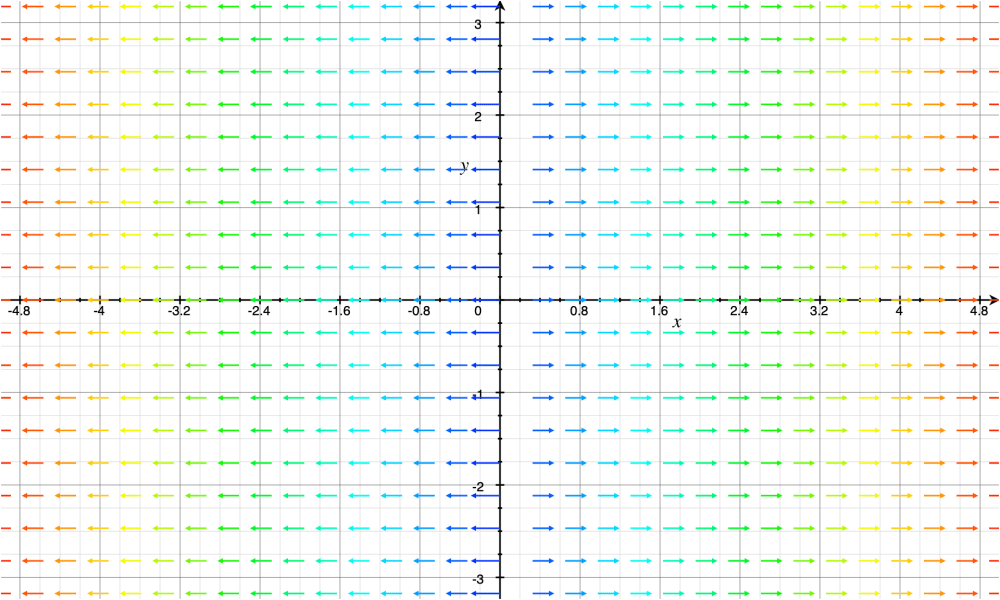

This means that the input force corresponds to a vector force field, which is basically a vector field. Whoa. Okay what’s a vector field? A vector field is just a continuous collection of vectors across space and time that vary with either co-ordinates or time derivatives of how fast the co-ordinates are being traversed, or just time in general. Thus at every point in space and for every value of time, a field is defined.

A vector field can be expressed as a vector whose components are functions of some continuous variable.

This vector field can be written as

F = <x,y>

meaning, both the right-left or horizontal component and the top-down or vertical component of the vector increase equally as you go along the X-axis and Y-axis respectively.

Input force is a vector field but all vector fields don’t represent force. Calling a vector field “force” isn’t also characterizing any physical phenomena. It’s just a name we’ve given to a vector field.

We need to figure out how this vector field interacts with physical phenomena. We know how the field varies with respect to an independent variable quantity, but we haven’t yet established what would physically happen to a particle placed at some point on the field.

Here’s where Newton’s Laws come into the picture.

They’re used to explain the way the ‘force field’ (vector field) interacts with physical objects.

Any particle can be approximated as a point mass when far enough from the particle. Thus if we do not consider the frictional or elastic forces present within the body that tend to deform it by storing energy or dissipate energy through contact forces (friction), the response of a body to a force imparted to it is purely kinetic in nature; the body is accelerated from rest. Thus all this means is, in our situation, if you hit a ball sitting idly on a frictionless table, it doesn’t change shape nor does it heat up due to friction, it just keeps moving.

The way the force field interacts with a point particle is by accelerating it. It is a fancy way of saying that the force makes it go faster and faster.

Why is the reaction of a particle to a force proportional to the derivative of its velocity? Why isn’t it proportional to the velocity of the particle itself? After all, forces make particles move, right? Why doesn’t the output force or the reaction of the particle to the input just be related to how fast it moves? Why is it instead related to how fast the speed changes?

This comes from basic observations of the world.

Let’s do a thought experiment where the force reaction is proportional to the velocity of the particle; F is proportional to v, where F is input force and v is the velocity of the particle.

Consider a situation where a ball is placed on a frictionless table. It is at rest, just idly sitting there. The net force acting on the ball is zero. Let F=v here. If you push the ball with an input F of magnitude 1, its speed changes from 0 to 1. If the force magnitude is 2, the speed is 2. If you stop forcing the ball, F=0, the ball stops, speed is also 0. This seems weird as you would have to keep pushing the ball for it to move. Once you stop pushing the ball, the ball stops. This is reminiscent of pushing a great boulder that is extremely heavy. But for this thought experiment, we have chosen to take a normal sized ball on a frictionless table.

In reality, if you push the ball just for an instant, it moves for a longer period and comes to a stop due to friction. If friction did not exist, it would have to keep moving even when the force does not exist.

Thus, if a particle’s reaction to some force is proportional to its velocity, it means that when an input force (function of some variable) is imparted to a particle, its reaction to the force causes it to move. Thus, when an input force is applied, its response will be its movement (velocity) with a magnitude proportional to that of the force, in the same direction.

Thus, this means that for the object to move with continuous velocity, there must be a continuous force acting on it as input, as the response is the continuous movement.

But again, as I’ve said above, this seems weird as you would have to keep pushing the ball for it to move. Once you stop pushing the ball, the ball stops.

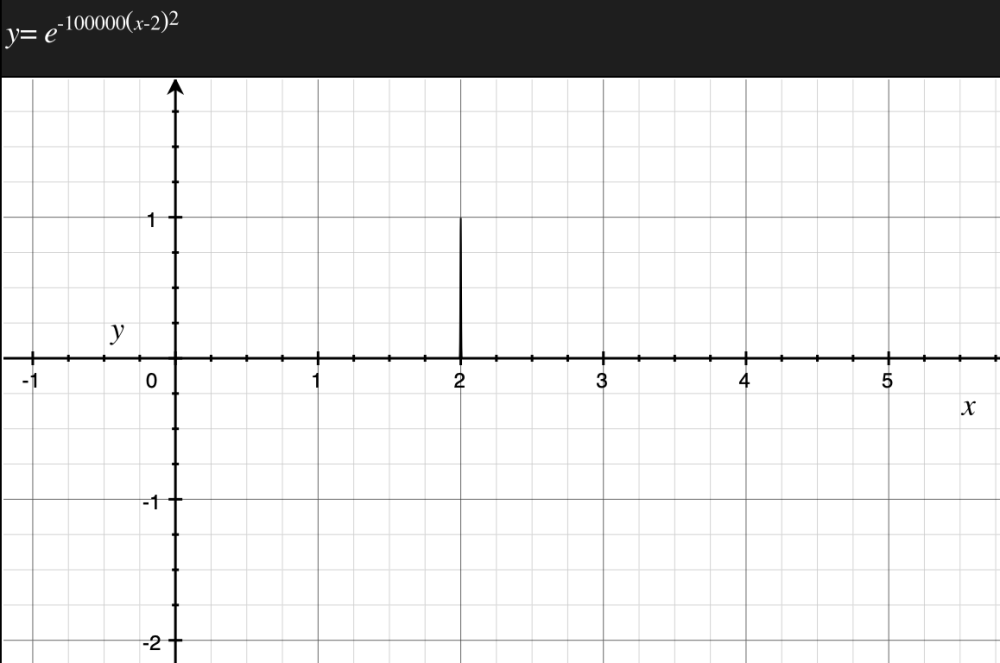

Since it is hard to do thought experiments with mathematical functions of high complexity, let us take the simple case of the input force being a force of a constant magnitude that acts only at time t=t0 (an arbitrary reference point for time), and is zero for all other values of time. Obviously in reality no force can be discrete, so let’s approximate a curve that fits this characteristic well. The best curve that does this is an exponentially rising and decaying curve that rises to achieve a maxima and then decays very quickly, preferably in the order of a very small period of time.

So let’s start squishing!

A little more!

Aaaand done!

Now we have a continuous curve that for all uses resembles a discrete curve. This is graphically the input force-time relationship we want!

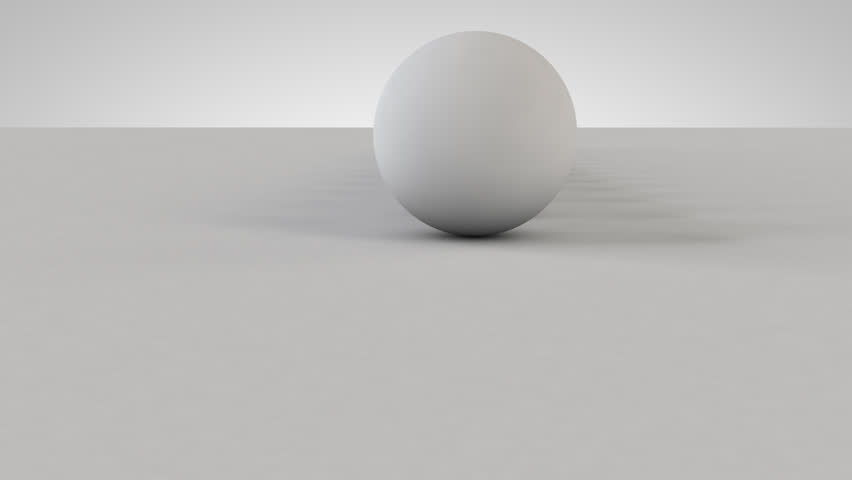

The physical realisation of this is to consider applying a force on a particle for a very short time, so short, that it appears to be discrete. A somewhat okay approximation of this would be to flick a particle at rest. Let us take a spherical particle/ball as it is symmetrical throughout.

In reality, we can see that if we flick or hit a ball at rest, it moves for a while before coming to a stop.

So, while the input force is applied only for a very small period of time, the ball moves for a considerably longer period of time.

Thus, if the velocity of the ball had been proportional to the input force, then it would have moved only when there was a force acting on it to make it move. Thus the movement of the ball would have existed only for the same short period of time that the force existed.

But we can see that that’s not the case.

We can see that the object moves faster when the force is present, despite the force not being applied for the whole time the particle is in motion; this whole scenario is of course only possible when we imagine a hypothetical frictionless surface, knowing that friction is some kind of force that brings objects in motion to a stop after a while.

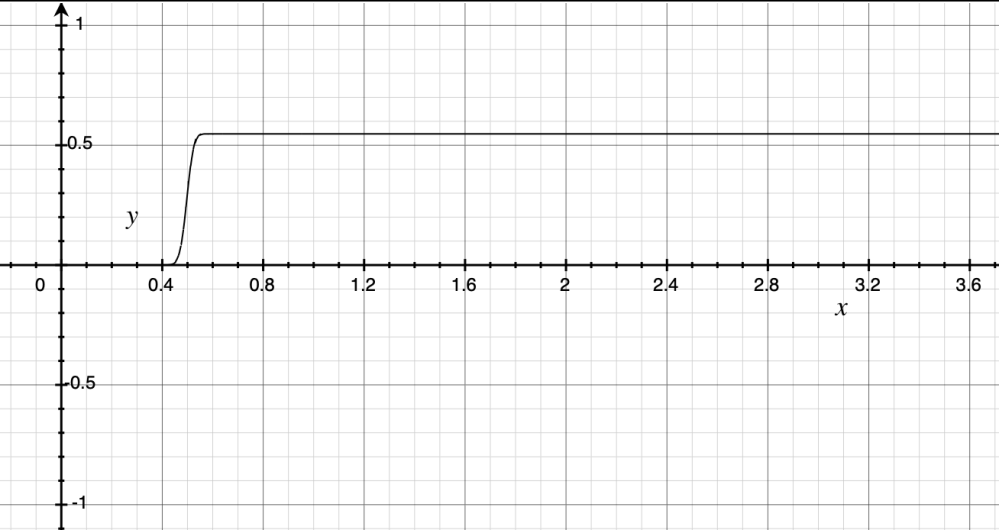

In an ideal, hypothetical situation where friction doesn’t exist on the surface where the particle is being ‘forced’, the particle’s velocity would increase when the input force exists, until it reaches a new value, then it moves uniformly at that value after the input force goes to zero.

In reality of course, we can still see the effect of the increasing velocity but instead of attaining a new velocity, the particle comes to stop due to the friction force pushing the particle in the opposite direction.

Why is the response of the particle not a function of its position?

Then for a particle to even stay at a position an input force would be required, which is obviously not so. If the particle’s at rest, there need not be a force acting on it to keep it that way.

What about the response being proportional to jerk?

Jerk is the third derivative of position. This is a fancy way of saying that it is a measure of how fast something accelerates. Meaning, it tells us how fast, the fastness of something changes. That’s a lot to take in!

Then, even for a force as engineered before, that is approximately discrete, the acceleration is going to increase until a new steady time invariant (constant with respect to time) value of acceleration is achieved. This is because jerk denotes change in acceleration with respect to time, and if there is a positive change for an extremely short while also, the positive change exists and a new acceleration value is reached.

But this means for an input force of a constant magnitude of energy, the particle is going to accelerate continuously, meaning its velocity and kinetic energy increase infinitely. This breaks the Law of Conservation of Energy and thus it can not be possible.

Thus the response can not be proportional to higher order derivatives of velocity except for the 1st: acceleration.

Drinks anyone?

Thus the only mathematical model (that satisfies observations of reality) of the response of a particle to an input force is, that it is proportional to the acceleration of the particle.

Let’s talk about the proportionality constant now. The Force input value divided by the constant gives us the output acceleration.

For a specific input force magnitude value, the acceleration value of a lighter object is higher compared to a heavier one. Thus as you increase the “heaviness” of the object, for a fixed input force value, the output acceleration decreases inversely. Thus this proportionality constant has to be related to how heavy the object is.

This is what we call “mass”. The measure of inertia. The tendency of something to resist change in motion.

Thus the response to any input force, or the output force is the product of the mass of the particle and the acceleration it experiences due to the input force.

F=ma.

Mind blowing blog ! Keep up the good work Anand! Keep on writing! 💗

LikeLike

Thanks ma! ❤

LikeLike